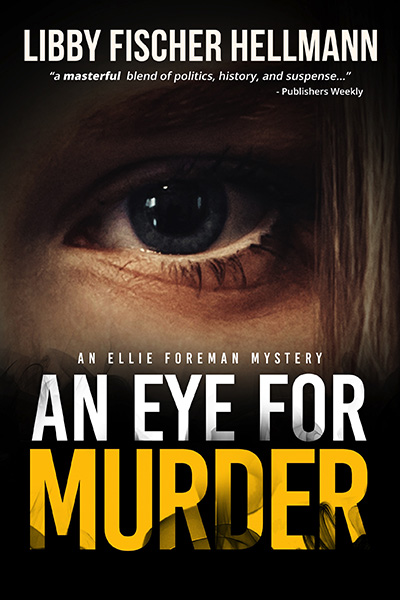

Series: The Ellie Foreman Series

Series: The Ellie Foreman SeriesRelease Date: 2002

Genre: Mystery Fiction

Buy the Book:

My books are still available wide, but you’ll find the best prices on my store, especially if you buy more than one novel. Check out the two and three book Bundles here:

Libby's Store

August, 1944, Prague is where the story begins with a seemingly casual exchange. But in wartime, is any act, any one thing, trivial?

Decades later, in contemporary Chicago, the consequences emerge through the medium of television. Documentary filmmaker Ellie Foreman gets a letter prompted by the success of her show “Celebrate Chicago.” One viewer was the elderly Ben Sinclair. When he suddenly dies, his landlady Mrs. Fleischman finds Ellie’s name among his effects and writes to her. Ellie, who hasn’t a clue about a connection to Ben, is curious. And she agrees to help dispose of Ben Sinclair’s possessions. She became a filmmaker to help people tell their stories.

The books and wartime relics Ben left behind—will they be enough to tell his? All too soon, Mrs. Fleischman dies. Then Ben’s things are stolen from Ellie’s suburban home. The single mom, working to move past her ex, doesn’t know what to think. But she has to scramble for work and is soon embroiled in producing a campaign video for a steel magnate running for a Republican seat in the Illinois Senate. Despite these distractions, Ellie stays focused on her odd link to the dead man and turns to her father, a retired lawyer with deep roots in Chicago’s Jewish community, for insights into the mystery of Ben Sinclair. In time, a terrifying scenario develops that reaches back into several pasts.

From the political present of the North Shore to the buried memories of the city’s ethnic neighborhoods, the components of Ben’s story eventually merge into an explosive climax.

- Nominee, Anthony Award for Best First Novel

- Winner, Readers’ Choice for Best First Novel (Love is Murder conference)

Reviews:

A masterful blend of politics, history, and suspense, this novel is well worth reading… sharp humor and vivid language… Ellie is an engaging amateur sleuth. Readers will hope they won’t have to wait too long for Ellie’s return.

—Publishers Weekly

A clever blend of thrills and humor… Hellmann has created a compelling group of believable characters…

—Chicago Sun-Times

Complicated… fascinating… Hellmann has a beautifully tuned ear… which makes many of her scenes seriously funny.

—Dick Adler, Chicago Tribune

Entertaining and well written… a surprising and satisfying conclusion… a clever thriller.

—Ted Hertel, Mystery News

Also in this series:

Excerpt:

Prague: May, 1944

The evening air was heavy and damp. Summer kept hanging on. The scent of rotting fish mixed with exhaust fumes as trucks cut through the narrow streets of the city. Nothing seemed clean anymore. It was hard to imagine Prague was once the crown jewel of the Hapsburg Empire.

He’d spent the afternoon checking the route. Strolling past Panska and the office that had housed the Prager Tagblatt until the Nazis shut it down. Past the Castle, the Palace, and the Basilica, with their jumble of Romanesque, Renaissance, and Baroque architecture. Trying to look unobtrusive. Just another Czech citizen out on a late summer day.

The city made him uncomfortable. Back home before the war, he’d prowled dark streets and alleys, courting danger, practically daring it to appear. But now, danger meant death if he was caught. He was careful to avoid people and crowds.

The restaurant smelled of stale beer, and the tables were coated with grime. Maybe it was the European tolerance for a state of clean that would make Westerners cringe. Or maybe it was the only way the people in occupied countries had to rebel against Nazi discipline. A few patrons had come in, old men mostly, their bodies shriveled with age. One hobbled on a cane.

After observing the place for an hour, the American decided it was safe to enter. He leaned in at the bar, a glass of beer in his hand, but his gut twisted every time someone glanced his way.

The door squeaked as someone came in. He turned around. The new arrival ordered a Schnapps. The bartender, busying himself with a glass and the bottle, didn’t look up. The man tossed his drink down in one gulp and thumped his glass on the bar. The bartender refilled it.

“The Kinski gardens are beautiful now, yes?” the new arrival said in German, looking down the bar.

The American replied in heavily-accented German. “I prefer the park this time of year.”

The new arrival shifted slightly, almost imperceptibly. “Yes. It is cooler there.”

After ten minutes and another Schnapps, the new arrival dug deep in his pocket, tossed a few coins on the bar, and walked out. The American stayed a few more minutes and then left also, turning toward the river. Dusk was upon him, dark shadows softening the edges of buildings. He was careful to make sure he wasn’t followed. Three streets north and two streets east. Just another citizen out for a walk.

As he passed the narrow cobblestone alley behind the museum, a voice from the shadows said softly, “Good evening, comrade.”

The American looked up, startled.

“Sorry. My little joke. ” His contact smiled. “We will speak in English. But we whisper.”

The American managed a nod. “What should I call you?”

He paused. “Kafka. And you?”

“You can call me Joe.”

“GI Joe.” Kafka’s smile faded. “It is unusual to see an American so far from home. Especially here. How did it come about?”

“I had work to do.”

“You have had a long journey.”

“I have been in Berlin. The East before that.”

“A freedom fighter. We honor you, Joe.”

He shrugged.

“So. I understand you have information for us?”

“How do I know it will get to the right place?”

“There is no guarantee. But we both know you did not agree to this meeting without—how do you say it—checking us out.”

Kafka was right. Joe had heard about the intelligence unit formed by the British and the Americans. Fighting the Germans by stealing codes. Infiltrating their ranks. Kafka worked for them, he’d been told. He took a breath. “You’ve heard of Josef Mengele?”

Kafka’s jaw tightened. “The Butcher of Auschwitz.”

“Yes.” Joe had learned for himself one sunny day not long ago. He remembered wondering how the sun had the nerve to keep shining.

“We have heard rumors of the obscene medical experiments,” Kafka said.

Joe nodded. “We thought the insanity belonged only to Hitler, Mengele, and the madmen here in Europe. But now…” He reached into his jacket and pulled out a sheaf of papers tied together with string. He untied them and handed them to Kafka.

Kafka stayed in the shadows, angling the documents toward a light that spilled into the alley. Joe couldn’t see them in the blackness. He didn’t need to. A report detailing the experiments. Sent with a cover letter to Reichsfuehrer Himmler, Carl Clauberg, and someone named Rauscher. And one other person.

He waited while the agent read what he knew by heart: “and to our friends on the other side of the ocean, whose financial and moral support has sustained us. We are united in working toward the same goals. May this research aid your efforts as well.”

Kafka looked up. His eyes glittered in the shadows. “How did you come by this?”

“I can’t tell you,” Joe said. It had been Magda’s doing. She had “intercepted” the courier. He owed her. “But I will vouch for its authenticity.”

“The name on this letter… the American. He is—”

“I know who he is.”

“Do you know him?”

“No.”

“I do. He is involved in the war effort. My superiors speak well of him.”

Joe squinted. “What are you trying to say?”

“They will not believe this.”

A chill edged up his spine. Everything he’d worked for was suddenly in jeopardy. “Does that mean you’re not going to pass it through channels?”

Kafka shrugged. “They will think it is disinformation. Calculated to make us respond.”

He opened his hand. “Give it back, then. I’ll handle it myself.”

Kafka moved the letter beyond his reach.

The American’s hand crept to his pocket, his fingers gripping the barrel of his Forty-Five. “I haven’t risked my fucking neck to see this buried. Not now.”

Kafka’s eyes stayed on Joe’s pocket. “I have an idea,” he said slowly. “Where are you from, comrade?”

He tilted his head. “What the—what does that matter?”

“You are from Chicago, yes?” Kafka moved away from the light.

“How did you know that?”

“Do you think we did not check you out as well?” Kafka smiled. “What is you Americans say? It is a small world, yes?”

Joe glared. “What does that mean?”

“I live there too. Since I left Germany. Where can I find you—in Chicago?”

Joe kept his grip on the gun. “Listen, pal, I’m not gonna—”

“Trust me. Your journey has not been in vain.”

Just then he heard the click of boots on the pavement. A group of Waffen SS troops, full of drink from a nearby tavern. He tried to grab the report, but Kafka edged behind him and slipped it inside his shirt.

“Well, comrade?” Kafka said quietly.

The American stiffened. Then he whispered hoarsely, “Miller’s. Davy Miller’s.”

He made himself small as the soldiers stumbled past the alley. When their beery laughs faded into the night, he turned around. Kafka was gone.

Chicago, The Present

The old man lifted his head at the sound. It was probably the dog sniffing outside his door, waiting for a treat. He folded the newspaper and pushed himself up from his chair. His landlady got the mutt last month. For security, she said. Some guard dog. He never barked and always wagged his damn tail when he saw the old man.

He didn’t mind. The dog was better company than its owner. He shuffled to the door, stopping to pull out a box of Milk Bones he’d stashed in the closet. He pictured the animal wriggling in pleasure as he waited for his treat. It struck him that the dog was his sole link to a life of warmth and affection. Well, life had always handed him the bent fork. But he’d survived. Like a sewer rat always on the move, he’d foraged what he needed, sometimes getting more, sometimes less.

But now survival wasn’t enough. His eyes moved to the newspaper. He’d somehow known it would come to this. You could never destroy the evil; it always grew back, like one of those lethal viruses, more virulent and dangerous than its previous incarnation. He had to act. Soon. He would launch a surgical strike, precisely timed for maximum impact. And this time, he would get results.

Clutching the dog treat in one hand, he opened the door with the other. Two men pushed their way in. One had a pony-tail and wore sunglasses; the other wore a fishing hat pulled low on his forehead. The man with the hat grabbed him in a hammerlock while the other pulled something out of his pocket. A syringe. The old man struggled feebly but he was no match for them. Pony-tail plunged the needle into his chest. The old man’s hands flew up. The dog biscuit fell from his hands and skittered across the floor.

Chapter One

I didn’t get the mail until late. Rachel and I were in the car driving home from school. “Honky Tonk Woman” was blaring out of the speakers, and I was thumping my hand on the wheel, thinking I had just enough time to chop onions and celery for a casserole before her piano lesson, when my twelve-year-old asked me about sex.

“Mom, have you ever had oral sex?”

“What was that, sweetheart?”

“Have you ever had oral sex?”

I nearly slammed on the brakes praying for something—anything—to say. But then I stole a look at her, strapped in the front seat, her blue eyes wide and innocent. Was she was testing me? Friends had been warning me sixth grade was a lot different these days.

I turned the radio down. “Who wants to know?”

“Oh, come on, Mom. Have you?”

I glanced over. Somehow her eyes didn’t look as innocent. I might even have seen the hint of a smirk. “Ask me again in about twenty years.”

“Muhtherrrr…”

Her face scrunched into that exasperated expression only pre-teen girls can produce. I remembered doing the same thing at her age. But then I was behaving just like my mother did, so I guess we were even. I changed the subject.

“How was school?”

She wriggled deep into the front seat, stretched out her arm, and turned up the radio. She punched all six buttons in turn, ending up at the oldies station it had been tuned to originally. “Two guys got into a fight at lunch.”

First sex. Now violence. This was a big day. “What happened?”

“You know Sammy Thornton, right?”

“Sure.” Everyone knew Sammy Thornton. A few years ago his older brother, Daniel, had rampaged through a predominantly Jewish neighborhood on the north side of Chicago and shot six Orthodox Jews. He shot two more people downstate before turning the gun on himself. Afterwards, it was discovered he had ties to a Neo-Nazi group in central Illinois. I remember huddling in front of the TV that Friday night, watching the horror unfold with Rachel, who, at nine, was asking the one question I couldn’t answer: Why? I remember feeling sorry for Sammy at the time, knowing that no matter how hard he struggled to rebuild his life, he would never escape being Dan Thornton’s brother.

“Joel Merrick is a friend of his.”

“I don’t think I know Joel.”

“He lives over on Summerfield. Has a sister in fourth grade.”

I shrugged.

“Well, Pete Nichols started calling Sammy a Nazi. Joel stuck up for him and told Pete to shut up. Then Pete called Joel a Nazi too, so Joel decked him.”

I turned onto our block. “Was anyone hurt?”

“Pete got a bloody nose, but he didn’t go to the nurse’s office.”

“What did the teachers do?”

Rachel was silent.

“Didn’t anyone say anything?” She shook her head. “Maybe someone should.”

“You can’t!” She wailed in dismay. “Mom, if you say anything, I’ll die.”

I parked in the driveway. “Okay. But I want you to know that Pete’s behavior was totally unacceptable. No has the right to lash out at people like that.” She looked over. “Hate is hate, no matter who it’s coming from.”

Rachel gathered her backpack and climbed out of the car. “Pete’s a jerk. Everyone knows that. And no one believes Sammy is a Nazi.”

I relaxed. Maybe I worried too much. Rachel was a resilient, self-assured kid—despite her messy upbringing. I unloaded a sack of groceries and took them into the house.

“So, Mom, have you had oral sex?”

Damn. That always happens when I get complacent. I set the groceries down on the kitchen table. Then I heard a giggle.

I turned around. “What’s so funny?”

“J.K, Mom.”

“Huh?”

“Just kidding.” She grabbed a can of pop from the refrigerator and dashed out.

Later that night after she went to bed, I called two friends to analyze how I’d handled the situation. Susan thought I’d done a great job, but Genna wasn’t so sure. She wanted me to call the Parent Hot Line. Genna is always telling people to open up to strangers. She’s a social worker.

By the time I settled down with a glass of wine, it was almost midnight. That’s when I remembered the mail. We live in a bedroom community twenty miles north of Chicago. I’d intended to remain an urban pioneer forever—until the day Rachel and I walked to the park from our Lakeview condo. Strolling by a sidewalk dumpster at the end of our block, my bright, curious three-year-old pointed to it and exclaimed, “Mommy, look, there’s an arm!” Sure enough, a human arm hung motionless over the edge. We moved to the suburbs six months later.

I sometimes think about moving back to the city, but the school system, despite the occasional incident, is one of the best in the state. And while the village I live in has minimal charm and less personality, it is safe enough to go outside at night. Even to the park.

The problem is that I don’t like getting the mail. There’s never anything besides bills. But tomorrow was Friday, and if I got the mail tonight, I could rationalize avoiding it again until Monday. I threw on a jacket—it was late April, but spring is just a theoretical concept in Chicago—and sprinted to the mailbox.

In between statements from Com Ed and the gas company was a large white envelope from the Chicago Special Events Bureau, a client for whom I’d produced a videotape. When I opened it, a smaller pale yellow envelope tagged with a post-it fell out.

Ellie: This came for you. Probably yet another piece of fan mail. The mayor says to quit it. You’re stealing his thunder. Dana

I smiled. The mayor’s office had commissioned an hour documentary for the city’s Millenium Celebration, and I was amazed when I won the bid. Celebrate Chicago turned out to be the best show I’ve ever produced: a lyrical, descriptive piece that traced the history of several city neighborhoods with stock footage, photos, and interviews. The show debuted at a city gala and is still running on cable. Though the stream of complimentary notes has dwindled to a trickle, Dana Novak, the Special Events Director, graciously forwards them to me.

I turned over the yellow envelope, noting the floral design embossed on the border. My name, Ellie Foreman, was hand-written in ink, in care of “Celebrate Chicago.” The return address said Lunt Street, Chicago. Lunt was in Rogers Park. I slit the envelope with a knife. Small, cramped writing filled the page.

Dear Ms. Foreman,

I hope this letter reaches you. I didn’t have your address. My name is Ruth Fleishman. We’ve never met, but I didn’t know where else to turn. For the past two years, I rented out a room to an elderly gentleman by the name of Ben Sinclair. Unfortunately, Mr. Sinclair passed away a few weeks ago. He doesn’t have any family that I know about. That’s why, when I found your name on a scrap of paper among his possessions, I thought you might be a relative or a friend. If you are, I would appreciate a call. I don’t think Mr. Sinclair left a will; however, there may be some sentimental value to the few things he did leave behind. I hope to hear from you soon.

Under the signature was a phone number. I poured another glass of wine. Ben Sinclair’s name wasn’t familiar, but we’d spoken to hundreds of people in dozens of neighborhoods during Celebrate Chicago. I should probably check with Brenda Kuhns, my researcher. She keeps meticulous notes.

Still, I was curious why a dead man would have my name. Despite the show, I’m no VIP, and I couldn’t imagine how my life intersected with that of a solitary old man who died alone in a boarding house.

The clock read four fifteen, and I couldn’t sleep. Maybe it was the wine. When alcohol turns into sugar, I get all geeked up. Or maybe it was the handful of chocolate chips I ate just before turning in. Or possibly it was a lingering unease about the letter. I rolled out of bed, checked on Rachel, and took the letter up to my office.

My office used to be the guest room before the divorce. It’s not big, but the view more than compensates for its size. Outside the window is a honey locust, and on breezy summer days, the sun shooting through the leaves creates sparkles and shimmers that humble any manmade pyrotechnics. If you peek through the leaves, you can see down the entire length of our block. Of course, nothing much happens on our block, but if it did, I’d be there to sound the alarm—my desk is right under the window. The only trade-off is a lack of space for overnight guests.

Works for me.

I booted up and ran through my show files, using the search command for “Ben Sinclair”. Nothing popped up. I opened Eudora and did the same thing with my e-mail. Nothing. I e-mailed Brenda and asked if the name meant anything to her.

I went into the bathroom, debating whether to take a sleeping pill. A fortyish face with gray eyes and wavy black hair—the yin to my blonde daughter’s yang—stared back at me in the mirror. I still had a decent body, thanks to walking, an occasional aerobics class, and worrying about Rachel. But the lines around my eyes were more like duck’s webbing than crow’s feet, and grey strands filigreed my hair.

I decided against a sleeping pill. Back in my office, I re-read Ruth Fleishman’s letter, then logged onto a white-pages site, which promised to give me the address and phone number of anyone in the country. I entered Ben Sinclair’s name. A mouse-click later, fifteen Ben Sinclairs across the country surfaced, each with an address and phone number. When I tried Benjamin Sinclair, another six names appeared. None of the listings were in the Chicago area. I printed them out anyway.

A set of headlights winked through the window shade, and the newspaper hit the front lawn with a plop. I yawned and shut down the computer.