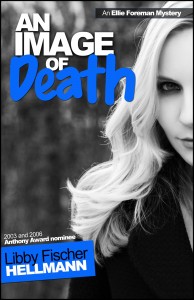

This ess ay was first published in Crimespree Magazine in 2005, but since I just got the rights back to AN IMAGE OF DEATH, I thought I’d share it. My visit there still resonates. It is a little long, so save it until you can read the whole thing.

ay was first published in Crimespree Magazine in 2005, but since I just got the rights back to AN IMAGE OF DEATH, I thought I’d share it. My visit there still resonates. It is a little long, so save it until you can read the whole thing.

The buildings rose out of the prairie as though the ground had suddenly coughed them up from some nether region. A few homes were scattered nearby, and a school sat to one side, but the compound, about twenty minutes from Racine, Wisconsin, loomed beside the road like a behemothwarning us we were entering a different world. We parked in an adjacent lot and climbed out. I’d been told to leave my purse in the car, so I swung my backpack up on my shoulder and headed inside.

I was surprised by the seemingly low level of security. Just one small metal detector, no search wands, no dogs. A beefy looking man behind a counter asked to see a photo ID. All the doors were locked, though, even the ladies room, and to get from the entrance hall into the meeting room, you passed through a small antechamber with glassed in walls and two doors. One door was locked before the other was opened.

I glanced into the meeting room. Almost forty women were there, waiting quietly, apparently content to let time pass. Clearly, this was no ordinary book club.

I’d been asked to come to the Robert Ellsworth Correction Center for women to talk about my third novel, An Image of Death. The invitation had been issued via Midge Green, the CRM at Barnes and Noble, Racine, WI. She and some of her friends had been visiting the jail regularly, bringing books and discussing them with inmates.

Ellsworth is home to approximately 300 female offenders. It’s a minimum security facility, and some of the women are on work release programs at nearby factories. About a year ago, two employees at the jail, Pam Petersen and DeNeal Erickson, decided to start a Book Club for the inmates. Within six months there were 25 members, and after a year, 50. Typically, the women would read the selected book, then divide into smaller groups to discuss the issues raised. Thanks to contributions and fund-raisers by B&N and others, the women have read several works, including Motherland by Fern Schumur Chapman and Seedfolks by Paul Fleischman. Image, however, was the first crime novel on their list.

Crime fiction for criminals? What was that all about? Who was I kidding? What could I, a woman who still gets the shakes when I get within twenty feet of a cop, tell them about crime or the criminal justice system?

The answer, I was told, was in Image. In the book an unidentified package is dropped on the doorstep of my amateur sleuth, video producer Ellie Foreman. Inside is a surveillance video that, when Ellie plays it, shows the murder of a young woman. Who that woman was and why the tape ended up with Ellie is the crux of the plot.

I’m not giving too much away by revealing that the woman killed on the tape wasn’t from this part of the world. Arin grew up in Armenia, and after marrying a Russian soldier, she moved to the Republic of Georgia. She lived in the lap of luxury as the wife of a Soviet army officer for a brief time—until the Soviet Union collapsed. Suddenly, her world was thrown into chaos, every trace of stability stripped away. Life became brutal, survival precarious. The choices facing Arin (and her best friend Mika) were made out of desperation. Arin became a diamond courier; Mika was forced into prostitution. Both had to contend with men whose need to survive themselves made them behave in aberrant, cruel ways.

It was this concept of choices—or the absence of them—that resonated with the teachers at the jail and prompted the invitation. The offenders in Ellsworth could relate to bad choices—or none at all. They wanted to hear about women in a similar predicament, explore their actions, compare them to their own. Would I please talk about that?

And so I nodded to the guard, sucked in a breath, and headed into the antechamber.

The first thing I noticed were three huge displays on mural paper taped to the wall. The first was titled “Russian Mafia”; the second “Foster Care” (Ellie is producing a video on the foster care system while she’s sleuthing); the third was “Transitioning back to mainstream society.” Each display was part photo montage, part hand-written text. As I browsed, I noted a lot of information about each topic: facts, figures, conclusions. Some of the information, especially on the “Transitioning” display was personal. They’d also drawn up a character tree, with each of my main characters and their character traits listed.

I started by telling them how and why I’d written An Image of Death—that I was intrigued by what happens to a society in the throes of radical change and that the best way to explore that was to tell the stories of a few individuals in the midst of the maelstrom. I talked about the characters and the role each played in the book. I talked about the notion of choices, and how Arin and Mika felt they didn’t have any. Almost every woman in the room nodded at that. One woman told me she felt I was writing her story. More nods all around. I decided it was time to let them talk, so I asked for questions.

I was overwhelmed by the response. It seemed as if every woman in the room had something to ask or say. Some asked questions about writing. Others asked questions about the characters. One woman told me she liked the information about foster care because she had two kids in the system now, and her goal was to reunite her family when she got out. Another woman asked how I did research, and another asked why David, Ellie’s boyfriend, made the choices he did.

I asked them about the displays. What had they learned about the Russian mafia, foster care, and transitioning back into society? Hands shot up. They’d learned that the Russian mafia wasn’t so much a monolithic organization as disparate gangs of thugs. That the violence and brutality they sanctioned made the Italian mafia look like kindergarten kids. That the foster care system wasn’t perfect, and in fact, was losing funding at an alarming rate, but it was better than the systems in other countries.

But the most touching moments were their comments about transitioning back into society. Person after person recounted how much Pam and DeNeal, the women who started the Book Club, had done for them. How valued they felt… some for the first time in their lives. How they felt that their opinions mattered. How wonderful the personal attention felt. How they would never forget the efforts their “teachers” had put into the Book Club and that they would carry this new found confidence back into the world. Pam and DeNeal were in the room, listening. They didn’t show much of a reaction, but I felt my throat get hot.

After the presentation, while I signed copies of Image, at least five women came up to tell me their stories. One of them said she was in her early sixties, but she didn’t look a day over fifty. Her hair was perfectly coiffed, her make-up expertly applied. None of the women wore uniforms, and she was dressed in a clean blouse tucked into a pair of slacks. She’d been seated in the first row and had said several times how much she connected to Image. When I asked why, she told me she’d been a business woman who owned three beauty salons outside Milwaukee. She’d married late in life—a man from Croatia. The relationship soon soured; he had a violent temper. When the US sent troops into Bosnia twelve years ago, he became enraged. He went after her and beat her for three hours. Something inside her snapped, and she grabbed a kitchen knife and stabbed him to death. She got twenty years, but after serving twelve of them, her sentence was reduced. She was getting out soon, she said, but while she was still there, she had started a salon at Ellsworth, and was teaching the women how to do hair.

I wished her luck. She wished me back the same.

As Midge drove us back to Racine, I tried to process the afternoon. Much of it was a blur—it had gone by so fast. The women asked more questions and were more receptive than I’d expected. I’d been concerned they wanted me to say something profound about crime fiction—after all, it’s not every day a crime fiction author talks to prison inmates—and I’d felt unequal to the task. But that wasn’t what happened. As we got to know each other, I felt more relaxed and sure-footed.

Still, I realized that, in one respect, I’d been right. The women of the Ellsworth Book Club weren’t ordinary. They were doing what many of us have ceased doing, forgotten, or relegated to the back of our minds. They were using books, the ideas sparked by them, and the experiences related to them, as catalysts—catalysts to make sense of their past and find hope for their future.

I was honored to be a tiny part of that process.