Europe, the main theater of World War Two, was thousands of miles across the Atlantic. But Nazi intelligence inserted German operatives into American cities and tried to convert German-Americans to Nazism well before the war broke out. During the war itself America saw plenty of espionage incidents and there was probably much more spy activity going on that the public was never told about. Here are just three of at least ten known incidents that took place during the war years.

Europe, the main theater of World War Two, was thousands of miles across the Atlantic. But Nazi intelligence inserted German operatives into American cities and tried to convert German-Americans to Nazism well before the war broke out. During the war itself America saw plenty of espionage incidents and there was probably much more spy activity going on that the public was never told about. Here are just three of at least ten known incidents that took place during the war years.

John Dasch’s Long Island Landing

In June 1942 a German U-boat delivered a group of saboteurs to the Long Island coast, led by George John Dasch. Their mission was to spend two years performing acts of violence, blowing up bridges, railways, and factories in New York City and across the East Coast in an operation dubbed ‘Pastorius’. The men were not experienced in espionage or sabotage and Hitler’s advisors were doubtful of success.

In June 1942 a German U-boat delivered a group of saboteurs to the Long Island coast, led by George John Dasch. Their mission was to spend two years performing acts of violence, blowing up bridges, railways, and factories in New York City and across the East Coast in an operation dubbed ‘Pastorius’. The men were not experienced in espionage or sabotage and Hitler’s advisors were doubtful of success.

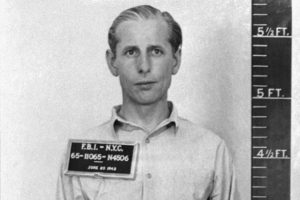

Luckily Hitler’s fears were realized. The submarine got stuck on a sandbar off Amagansett and local Coast Guard officer John Cullen discovered them. Dasch unsuccessfully tried to bribe Cullen, who reported the incident, and the spies’ explosives, German uniforms, and German cigarettes were later dug up on the beach.

By that time Dasch and his group had reached New York City, but Dasch got spooked and turned in his fellow spies, as well as himself. He wasn’t executed like the rest but after three decades in jail, he was finally deported back to West Germany in 1948.

Guenther Rumrich’s famous passport scam

Guenter Rumrich was born in my adopted home town, Chicago but was raised in Germany. Returning to the States in the late 1920s, he served in the US Medical Corps in Panama before deserting in 1936. He became suspect thanks to a Scottish woman, Jessie Jordan, who was already under surveillance by Britain’s MI-5 as a potential mail drop, passing letters between Nazi spies in the UK and US. When ‘Mr. Crown’, one of her contacts, turned out to be a code name for Rumrich, he was immediately put under surveillance.

Guenter Rumrich was born in my adopted home town, Chicago but was raised in Germany. Returning to the States in the late 1920s, he served in the US Medical Corps in Panama before deserting in 1936. He became suspect thanks to a Scottish woman, Jessie Jordan, who was already under surveillance by Britain’s MI-5 as a potential mail drop, passing letters between Nazi spies in the UK and US. When ‘Mr. Crown’, one of her contacts, turned out to be a code name for Rumrich, he was immediately put under surveillance.

In early 1938 Rumrich phoned the NYC Passport Office pretending to be the Undersecretary of State, asking for 35 blank passports. The clerk was suspicious and reported the call to the authorities. Rumrich was quickly arrested and became notorious as America’s first major pre-war spy. He gave up his fellow spies, who were also arrested, and was given a two year jail sentence as a reward for co-operating. The case, however, alerted the nation about America’s vulnerability to espionage and the government acted fast to close a bunch of loopholes.

Erich Gimpel and William Colepaugh’s Operation Magpie

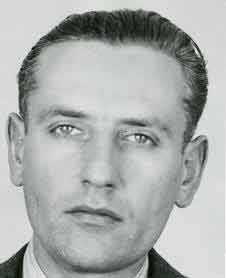

Late 1944 saw two German agents landing in America tasked with gathering intelligence on the US military and delaying the development of the atomic bomb. Erich Gimpel and William Colepaugh were keen but inexperienced in spycraft. A U-boat dropped them off at Bar Harbor in Maine, wearing completely unsuitable clothing for the time of year and carrying conspicuously expensive luggage packed with fake IDs, firearms, cameras, cash, and diamonds.

Late 1944 saw two German agents landing in America tasked with gathering intelligence on the US military and delaying the development of the atomic bomb. Erich Gimpel and William Colepaugh were keen but inexperienced in spycraft. A U-boat dropped them off at Bar Harbor in Maine, wearing completely unsuitable clothing for the time of year and carrying conspicuously expensive luggage packed with fake IDs, firearms, cameras, cash, and diamonds.

Arriving in New York City by train, the pair devolved into chaos. Colepaugh, an unstable alcoholic, immediately went on a bender, to the disgust of his partner in crime, and spent large amounts of the money they’d set aside for expenses. Colepaugh and a female companion he’d found along the way, eventually ran off with the remaining cash – more than $40,000 – and after a monster of a Christmas binge gave himself up to the FBI. Neither he nor Gimpel had done any actual spying, and like so many of his cowardly predecessors Colepaugh spilled the beans, telling the authorities everything he knew.

Both men were sentenced to death, but the war ended before they could be executed and they ended up in jail. Gimpel was released in 1955 and returned to West Germany, Colepaugh qualified for parole in 1960, and moved to Pennsylvania.

Other WW2 German spies on US soil

German Abwehr agent Lilly Stein recruited agents in New York, posing as a dress shop owner. Nazi spy Hermann W. Lang worked in the Carl L. Norden Corp. factory and spied on the progress of the company’s innovative new bombsight. The mission of the Ponte Vedra foursome was simple: commit acts of sabotage and terrorism on Jewish owned shops and destroy New York City’s water system. And maybe most famously, Fritz Duquesne and his 33-strong Spy Ring were all arrested in what became the biggest round up of foreign spies in the US, thanks to Double Agent William Sebold who worked with the FBI to expose them. The Duquesne spies were all convicted, but William Sebold himself disappeared, and his fate remains a mystery. Cary Grant starred in a 1945 film, “The House on 92nd Street,” which was based on the Spy Ring.

Happily, most of these German spies were inexperienced, several were unstable, a couple may actually have been mentally ill, and none of the failed plots made much of an impact on the allies’ progress. If they’d been better suited to the job, who knows what might have happened?

You can find more espionage stories (fiction this time) in War, Spies, and Bobby Sox: Stories about World War Two at Home, which will be released Feb. 28th.