“Good writing is supposed to evoke sensation in the reader – not the fact that it is raining, but the feeling of being rained upon.” E. L. Doctorow

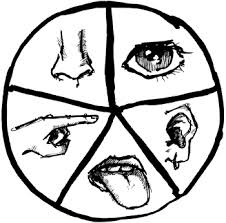

I love that definition. Sensory detail succeeds when a writer uses the senses of touch, taste, sight, smell and sound to create a visceral, emotional reaction from the reader. In a way, you could think of sensory details as a black and white movie. Without them the film may still be complete, logical, even compelling. But when you add them, everything turns to stunning color.

I love that definition. Sensory detail succeeds when a writer uses the senses of touch, taste, sight, smell and sound to create a visceral, emotional reaction from the reader. In a way, you could think of sensory details as a black and white movie. Without them the film may still be complete, logical, even compelling. But when you add them, everything turns to stunning color.

Despite the fact that sensory details are an important tool, if you take them too far you drift from storytelling into prose or even poetry. So how much is enough? Can you pin it down to a certain number per page, per paragraph, per scene, per chapter? And is such a thing as too much sensory detail, If so,how do you know?

Other Authors on sensory detail

Reading Like a Writer by Francine Prose is a great place to start. (Btw, I don’t normally suggest writers read books on writing—I think writers should write. But I make an exception for her.) An excerpt from a review in The Guardian, a respected British newspaper, says:

“Where this book really takes off is with Prose’s quite brilliant analysis of the power of detail in fiction. Turning to Kafka, she unpicks the famous opening of The Metamorphosis to show us that what makes us believe that Gregor Samsa really has turned into an insect is not the description of his armour-plated back but the picture that he has hung on his wall, of a lady in a fur stole. “Believing in this picture, we begin to believe in Samsa and in the possibility that he could turn into a bug.” It is the ordinary that makes us believe the impossible.”

So, less is more. To back up her message, in chapter eight Prose explains how just one or two important details can make “a much more memorable impression than a barrage of description”.

In her book Writing Fiction, Janet Burroway says, “If you write abstractions or judgments, you are writing an essay, whereas if you let us use our senses and form our own interpretations, we will be involved as participants in a real way.”

True, but a post by scientist turned science writer Jyoti Madhusoodanan on The Open Notebook site says you can mix abstract ideas and sensory detail. “Memorable stories captivate not only because they hold our intellectual attention, but also because they grab us by the senses, weaving smell, touch and taste through abstract concepts.”

And according to C. S Lakin, “Novelists can evoke smells and sensations in a way a movie can’t. Sure, a movie can show a plate of mouthwatering pizza, and that visual can set out stomach growling. Yet, a novelist can express from the character’s POV how that pizza smells and looks and makes her feel. If done well, our mouths will water as well while we read the passage, and we may even need to get up and raid the refrigerator.”

Each writer above adds something important to the mix. You don’t want readers to drown in fine detail, or lose the plot because you are too busy describing the sunset. And yet, there are times when an abstract idea should be expanded through sensory detail. And I’m all for raiding the refrigerator.

Four guidelines

So… how do I use them?

First and foremost, whenever I find myself telling a character’s thoughts or emotions, I try to show them instead, using sensory details. Instead of saying, “she was confused” I’ll change it to something like “She tilted her head to the side” or “Her brow furrowed, and she took a few aimless steps.”

OK, that’s pretty common. Most writers do the same thing.

Second, I use sensory details to support action and plot. When lyrical writing is used out of context, it’s irrelevant. But when it’s germane to the action, it can bring the scene to life. For example, if someone’s about to get shot, who cares what color the flowers are? But if the flowers are poisonous and someone is about to eat one, you can afford to wax a little lyrical.

Third, occasionally I’ll use sensory details as a metaphor to suggest a deeper meaning for the reader. As an example, using a brief but powerful description of a storm to hint that stormy emotional times are on the way. A cautionary note: you need to take care that you don’t overdo it.

Finally, I use them to make a setting more intense and vivid. Maybe it’s the smell of woodsmoke on a fall day. (Smell is probably the most underrated sensory tool, I think). Or the fishy goop in the waves crashing onto the shore. Again, it’s a balancing act how far to go.

How much/how often?

How many descriptive details can you use in a particular scene, page, or paragraph? There are no hard and fast rules. Sometimes you only need one beautifully chosen detail in a scene, particularly in genre novels. Other times you’ll want to explore all five senses. But when it’s the “first” time I’m dealing with a significant situation, action, place, or character, I try for three sentences of description, each using a different sense, each a little more distinctive than the one before. And when I can make that third phrase a simile or metaphor that reveals something unique about the character or situation, I’m a happy camper.

As I said, though, there are no rules. Here is one of my favorite passages in crime fiction. It uses sensory details (and rhythm… and language… ) in every sentence.

“I like bars just after they open for the evening. When the air inside is still cool and clean and everything is shiny and the barkeep is giving himself that last look in the mirror to see if his tie is straight and his hair is smooth. I like the neat bottles on the bar back and the lovely shining glasses and the anticipation. I like to watch the man mix the first one of the evening and put it down on a crisp mat and put the little folded napkin beside it. I like to taste it slowly. The first quiet drink of the evening in a quiet bar—that’s wonderful.” Raymond Chandler, THE LONG GOODBYE

What, Me Worry?

Btw, most of the time I can’t come up with every detail on a first draft. When I’m concentrating on developing the story, cogent words or images are sometimes the last thing on my mind. I’m learning not to worry about it. In fact, I know some writers who don’t even try to add sensory details until they’re revising. Bottom line: it doesn’t matter when in the writing process you do it. As long as you do.

What do you think? Do you have any rules? Or do you just let them emerge when they do?